The planning for 2023 began straightaway, at what in hindsight was a moment of irrational exuberance.

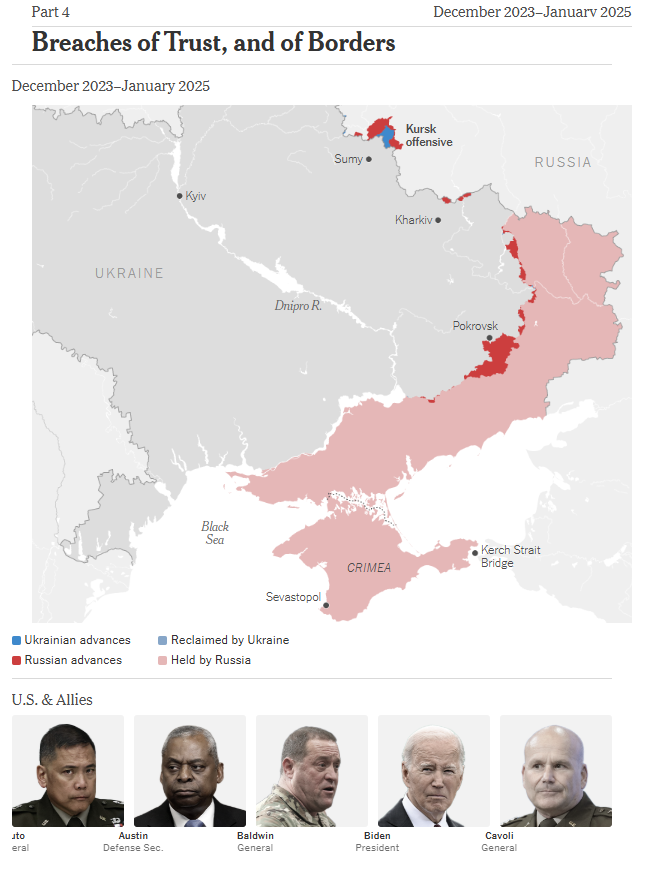

Ukraine controlled the west banks of the Oskil and Dnipro rivers. Within the coalition, the prevailing wisdom was that the 2023 counteroffensive would be the war’s last: The Ukrainians would claim outright triumph, or Mr. Putin would be forced to sue for peace.

“We’re going to win this whole thing,” Mr. Zelensky told the coalition, a senior American official recalled.

To accomplish this, General Zabrodskyi explained as the partners gathered in Wiesbaden in late autumn, General Zaluzhny was once again insisting that the primary effort be an offensive toward Melitopol, to strangle Russian forces in Crimea — what he believed had been the great, denied opportunity to deal the reeling enemy a knockout blow in 2022.

And once again, some American generals were preaching caution.

At the Pentagon, officials worried about their ability to supply enough weapons for the counteroffensive; perhaps the Ukrainians, in their strongest possible position, should consider cutting a deal. When the Joint Chiefs chairman, General Milley, floated that idea in a speech, many of Ukraine’s supporters (including congressional Republicans, then overwhelmingly supportive of the war) cried appeasement.

In Wiesbaden, in private conversations with General Zabrodskyi and the British, General Donahue pointed to those Russian trenches being dug to defend the south. He pointed, too, to the Ukrainians’ halting advance to the Dnipro just weeks before. “They’re digging in, guys,” he told them. “How are you going to get across this?”

What he advocated instead, General Zabrodskyi and a European official recalled, was a pause: If the Ukrainians spent the next year, if not longer, building and training new brigades, they would be far better positioned to fight through to Melitopol.

The British, for their part, argued that if the Ukrainians were going to go anyway, the coalition needed to help them. They didn’t have to be as good as the British and Americans, General Cavoli would say; they just had to be better than the Russians.

There would be no pause. General Zabrodskyi would tell General Zaluzhny, “Donahue is right.” But he would also admit that “nobody liked Donahue’s recommendations, except me.”

And besides, General Donahue was a man on the way out.

The 18th Airborne’s deployment had always been temporary. There would now be a more permanent organization in Wiesbaden, the Security Assistance Group-Ukraine, call sign Erebus — the Greek mythological personification of darkness.

That autumn day, the planning session and their time together done, General Donahue escorted General Zabrodskyi to the Clay Kaserne airfield. There he presented him with an ornamental shield — the 18th Airborne dragon insignia, encircled by five stars.

The westernmost represented Wiesbaden; slightly to the east was the Rzeszów-Jasionka Airport. The other stars represented Kyiv, Kherson and Kharkiv — for General Zaluzhny and the commanders in the south and east.

And beneath the stars, “Thanks.”

“I asked him, ‘Why are you thanking me?’” General Zabrodskyi recalled. “‘I should say thank you.’”

General Donahue explained that the Ukrainians were the ones fighting and dying, testing American equipment and tactics and sharing lessons learned. “Thanks to you,” he said, “we built all these things that we never could have.”

Shouting through the airfield wind and noise, they went back and forth about who deserved the most thanks. Then they shook hands, and General Zabrodskyi disappeared into the idling C-130.

The “new guy in the room” was Lt. Gen. Antonio A. Aguto Jr. He was a different kind of commander, with a different kind of mission.

General Donahue was a risk taker. General Aguto had built a reputation as a man of deliberation and master of training and large-scale operations. After the seizure of Crimea in 2014, the Obama administration had expanded its training of the Ukrainians, including at a base in the far west of the country; General Aguto had overseen the program. In Wiesbaden, his No. 1 priority would be preparing new brigades. “You’ve got to get them ready for the fight,” Mr. Austin, the defense secretary, told him.

That translated to greater autonomy for the Ukrainians, a rebalancing of the relationship: At first, Wiesbaden had labored to win the Ukrainians’ trust. Now the Ukrainians were asking for Wiesbaden’s trust.

An opportunity soon presented itself.

Ukrainian intelligence had detected a makeshift Russian barracks at a school in occupied Makiivka. “Trust us on this,” General Zabrodskyi told General Aguto. The American did, and the Ukrainian recalled, “We did the full targeting process absolutely independently.” Wiesbaden’s role would be limited to providing coordinates.

A satellite image of a school in occupied Makiivka where Russians had established a barracks. Maxar Technologies

The site after a strike that was aided by U.S. intelligence. Maxar Technologies

In this new phase of the partnership, U.S. and Ukrainian officers would still meet daily to set priorities, which the fusion center turned into points of interest. But Ukrainian commanders now had a freer hand to use HIMARS to strike additional targets, fruit of their own intelligence — if they furthered agreed-upon priorities.

“We will step back and watch, and keep an eye on you to make sure that you don’t do anything crazy,” General Aguto told the Ukrainians. “The whole goal,” he added, “is to have you operate on your own at some point in time.”

Echoing 2022, the war games of January 2023 yielded a two-pronged plan.

The secondary offensive, by General Syrsky’s forces in the east, would be focused on Bakhmut — where combat had been smoldering for months — with a feint toward the Luhansk region, an area annexed by Mr. Putin in 2022. That maneuver, the thinking went, would tie up Russian forces in the east and smooth the way for the main effort, in the south — the attack on Melitopol, where Russian fortifications were already rotting and collapsing in the winter wet and cold.

But problems of a different sort were already gnawing at the new-made plan.

General Zaluzhny may have been Ukraine’s supreme commander, but his supremacy was increasingly compromised by his competition with General Syrsky. According to Ukrainian officials, the rivalry dated to Mr. Zelensky’s decision, in 2021, to elevate General Zaluzhny over his former boss, General Syrsky. The rivalry had intensified after the invasion, as the commanders vied for limited HIMARS batteries. General Syrsky had been born in Russia and served in its army; until he started working on his Ukrainian, he had generally spoken Russian at meetings. General Zaluzhny sometimes derisively called him “that Russian general.”

The Americans knew General Syrsky was unhappy about being dealt a supporting hand in the counteroffensive. When General Aguto called to make sure he understood the plan, he responded, “I don’t agree, but I have my orders.”

The counteroffensive was to begin on May 1. The intervening months would be spent training for it. General Syrsky would contribute four battle-hardened brigades — each between 3,000 and 5,000 soldiers — for training in Europe; they would be joined by four brigades of new recruits.

The general had other plans.

In Bakhmut, the Russians were deploying, and losing, vast numbers of soldiers. General Syrsky saw an opportunity to engulf them and ignite discord in their ranks. “Take all new guys” for Melitopol, he told General Aguto, according to U.S. officials. And when Mr. Zelensky sided with him, over the objections of both his own supreme commander and the Americans, a key underpinning of the counteroffensive was effectively scuttled.

Now the Ukrainians would send just four untested brigades abroad for training. (They would prepare eight more inside Ukraine.) Plus, the new recruits were old — mostly in their 40s and 50s. When they arrived in Europe, a senior U.S. official recalled, “All we kept thinking was, This is not great.”

The Ukrainian draft age was 27. General Cavoli, who had been promoted to supreme allied commander for Europe, implored General Zaluzhny to “get your 18-year-olds in the game.” But the Americans concluded that neither the president nor the general would own such a politically fraught decision.

A parallel dynamic was at play on the American side.

The previous year, the Russians had unwisely placed command posts, ammunition depots and logistics centers within 50 miles of the front lines. But new intelligence showed that the Russians had now moved critical installations beyond HIMARS’ reach. So Generals Cavoli and Aguto recommended the next quantum leap, giving the Ukrainians Army Tactical Missile Systems — missiles, known as ATACMS, that can travel up to 190 miles — to make it harder for Russian forces in Crimea to help defend Melitopol.

ATACMS were a particularly sore subject for the Biden administration. Russia’s military chief, General Gerasimov, had indirectly referred to them the previous May when he warned General Milley that anything that flew 190 miles would be breaching a red line. There was also a question of supply: The Pentagon was already warning that it would not have enough ATACMS if America had to fight its own war.

The message was blunt: Stop asking for ATACMS.

Underlying assumptions had been upended. Still, the Americans saw a path to victory, albeit a narrowing one. Key to threading that needle was beginning the counteroffensive on schedule, on May 1, before the Russians repaired their fortifications and moved more troops to reinforce Melitopol.

But the drop-dead date came and went. Some promised deliveries of ammunition and equipment had been delayed, and despite General Aguto’s assurances that there was enough to start, the Ukrainians wouldn’t commit until they had it all.

At one point, frustration rising, General Cavoli turned to General Zabrodskyi and said: “Misha, I love your country. But if you don’t do this, you’re going to lose the war.”

“My answer was: ‘I understand what you are saying, Christopher. But please understand me. I’m not the supreme commander. And I’m not the president of Ukraine,’” General Zabrodskyi recalled, adding, “Probably I needed to cry as much as he did.”

At the Pentagon, officials were beginning to sense some graver fissure opening. General Zabrodskyi recalled General Milley asking: “Tell me the truth. Did you change the plan?”

“No, no, no,” he responded. “We did not change the plan, and we are not going to.”

When he uttered these words, he genuinely believed he was telling the truth.

In late May, intelligence showed the Russians rapidly building new brigades. The Ukrainians didn’t have everything they wanted, but they had what they thought they needed. They would have to go.

General Zaluzhny outlined the final plan at a meeting of the Stavka, a governmental body overseeing military matters. General Tarnavskyi would have 12 brigades and the bulk of ammunition for the main assault, on Melitopol. The marine commandant, Lt. Gen. Yurii Sodol, would feint toward Mariupol, the ruined port city taken by the Russians after a withering siege the year before. General Syrsky would lead the supporting effort in the east around Bakhmut, recently lost after months of trench warfare.

Then General Syrsky spoke. According to Ukrainian officials, the general said he wanted to break from the plan and execute a full-scale attack to drive the Russians from Bakhmut. He would then advance eastward toward the Luhansk region. He would, of course, need additional men and ammunition.

The Americans were not told the meeting’s outcome. But then U.S. intelligence observed Ukrainian troops and ammunition moving in directions inconsistent with the agreed-upon plan.

Soon after, at a hastily arranged meeting on the Polish border, General Zaluzhny admitted to Generals Cavoli and Aguto that the Ukrainians had in fact decided to mount assaults in three directions at once.

“That’s not the plan!” General Cavoli cried.

What had happened, according to Ukrainian officials, was this: After the Stavka meeting, Mr. Zelensky had ordered that the coalition’s ammunition be split evenly between General Syrsky and General Tarnavskyi. General Syrsky would also get five of the newly trained brigades, leaving seven for the Melitopol fight.

“It was like watching the demise of the Melitopol offensive even before it was launched,” one Ukrainian official remarked.

Fifteen months into the war, it had all come to this tipping point.

“We should have walked away,” said a senior American official.

But they would not.

“These decisions involving life and death, and what territory you value more and what territory you value less, are fundamentally sovereign decisions,” a senior Biden administration official explained. “All we could do was give them advice.”

The leader of the Mariupol assault, General Sodol, was an eager consumer of General Aguto’s advice. That collaboration produced one of the counteroffensive’s biggest successes: After American intelligence identified a weak point in Russian lines, General Sodol’s forces, using Wiesbaden’s points of interest, recaptured the village of Staromaiorske and nearly eight square miles of territory.

For the Ukrainians, that victory posed a question: Might the Mariupol fight be more promising than the one toward Melitopol? But the attack stalled for lack of manpower.

The problem was laid out right there on the battlefield map in General Aguto’s office: General Syrsky’s assault on Bakhmut was starving the Ukrainian army.

General Aguto urged him to send brigades and ammunition south for the Melitopol attack. But General Syrsky wouldn’t budge, according to U.S. and Ukrainian officials. Nor would he budge when Yevgeny Prigozhin, whose Wagner paramilitaries had helped the Russians capture Bakhmut, rebelled against Mr. Putin’s military leadership and sent forces racing toward Moscow.

U.S. intelligence assessed that the rebellion could erode Russian morale and cohesion; intercepts detected Russian commanders surprised that the Ukrainians weren’t pushing harder toward tenuously defended Melitopol, a U.S. intelligence official said.

But as General Syrsky saw it, the rebellion validated his strategy of sowing division by impaling the Russians in Bakhmut. To send some of his forces south would only undercut it. “I was right, Aguto. You were wrong,” an American official recalls General Syrsky saying and adding, “We’re going to get to Luhansk.”

Mr. Zelensky had framed Bakhmut as the “fortress of our morale.” In the end, it was a blood-drenched demonstration of the outmanned Ukrainians’ predicament.

Though counts vary wildly, there is little question that the Russians’ casualties — in the tens of thousands — far outstripped the Ukrainians’. Yet General Syrsky never did recapture Bakhmut, never did advance toward Luhansk. And while the Russians rebuilt their brigades and soldiered on in the east, the Ukrainians had no such easy source of recruits. (Mr. Prigozhin pulled his rebels back before reaching Moscow; two months later, he died in a plane crash that American intelligence believed had the hallmarks of a Kremlin-sponsored assassination.)

Which left Melitopol.

A primary virtue of the Wiesbaden machine was speed — shrinking the time from point of interest to Ukrainian strike. But that virtue, and with it the Melitopol offensive, was undermined by a fundamental shift in how the Ukrainian commander there used those points of interest. He had substantially less ammunition than he had planned for; instead of simply firing, he would now first use drones to confirm the intelligence.

This corrosive pattern, fueled, too, by caution and a deficit of trust, came to a head when, after weeks of grindingly slow progress across a hellscape of minefields and helicopter fire, Ukrainian forces approached the occupied village of Robotyne.

American officials recounted the ensuing battle. The Ukrainians had been pummeling the Russians with artillery; American intelligence indicated they were pulling back.

“Take the ground now,” General Aguto told General Tarnavskyi.

But the Ukrainians had spotted a group of Russians on a hilltop.

In Wiesbaden, satellite imagery showed what looked like a Russian platoon, between 20 and 50 soldiers — to General Aguto hardly justification to slow the march.

General Tarnavskyi, though, wouldn’t move until the threat was eliminated. So Wiesbaden sent the Russians’ coordinates and advised him to simultaneously open fire and advance.

Instead, to verify the intelligence, General Tarnavskyi flew reconnaissance drones over the hilltop.

Which took time. Only then did he order his men to fire.

And after the strike, he once again dispatched his drones, to confirm the hilltop was indeed clear. Then he ordered his forces into Robotyne, which they seized on Aug. 28.

The back-and-forth had cost between 24 and 48 hours, officers estimated. And in that time, south of Robotyne, the Russians had begun building new barriers, laying mines and sending reinforcements to halt Ukrainian progress. “The situation was changed completely,” General Zabrodskyi said.

General Aguto yelled at General Tarnavskyi: Press on. But the Ukrainians had to rotate troops from the front lines to the rear, and with only the seven brigades, they weren’t able to bring in new forces fast enough to keep going.

The Ukrainian advance, in fact, was slowed by a mix of factors. But in Wiesbaden, the frustrated Americans kept talking about the platoon on the hill. “A damned platoon stopped the counteroffensive,” one officer remarked.

The Ukrainians would not make it to Melitopol. They would have to scale back their ambitions.

Now their objective would be the small occupied city of Tokmak, about halfway to Melitopol, close to critical rail lines and roadways.

General Aguto had given the Ukrainians greater autonomy. But now he crafted a detailed artillery plan, Operation Rolling Thunder, that prescribed what the Ukrainians should shoot, with what and in what order, according to U.S. and Ukrainian officials. But General Tarnavskyi objected to some targets, insisted on using drones to verify points of interest and Rolling Thunder rumbled to a halt.

Desperate to salvage the counteroffensive, the White House had authorized a secret transport of a small number of cluster warheads with a range of about 100 miles, and General Aguto and General Zabrodskyi devised an operation against Russian attack helicopters threatening General Tarnavskyi’s forces. At least 10 helicopters were destroyed, and the Russians pulled all their aircraft back to Crimea or the mainland. Still, the Ukrainians couldn’t advance.

The Americans’ last-ditch recommendation was to have General Syrsky take over the Tokmak fight. That was rejected. They then proposed that General Sodol send his marines to Robotyne and have them break through the Russian line. But instead General Zaluzhny ordered the marines to Kherson to open a new front in an operation the Americans counseled was doomed to fail — trying to cross the Dnipro and advance toward Crimea. The marines made it across the river in early November but ran out of men and ammunition. The counteroffensive was supposed to deliver a knockout blow. Instead, it met an inglorious end.

General Syrsky declined to answer questions about his interactions with American generals, but a spokesman for the Ukrainian armed forces said, “We do hope that the time will come, and after the victory of Ukraine, the Ukrainian and American generals you mentioned will perhaps jointly tell us about their working and friendly negotiations during the fighting against Russian aggression.”

Andriy Yermak, head of the presidential office of Ukraine and arguably the country’s second-most-powerful official, told The Times that the counteroffensive had been “primarily blunted” by the allies’ “political hesitation” and “constant” delays in weapons deliveries.

But to another senior Ukrainian official, “The real reason why we were not successful was because an improper number of forces were assigned to execute the plan.”

Either way, for the partners, the counteroffensive’s devastating outcome left bruised feelings on both sides. “The important relationships were maintained,” said Ms. Wallander, the Pentagon official. “But it was no longer the inspired and trusting brotherhood of 2022 and early 2023.”

Shortly before Christmas, Mr. Zelensky rode through the Wiesbaden gates for his maiden visit to the secret center of the partnership.

Entering the Tony Bass Auditorium, he was escorted past trophies of shared battle — twisted fragments of Russian vehicles, missiles and aircraft. When he climbed to the walkway above the former basketball court — as General Zabrodskyi had done that first day in 2022 — the officers working below burst into applause.

Yet the president had not come to Wiesbaden for celebration. In the shadow of the failed counteroffensive, a third, hard wartime winter coming on, the portents had only darkened. To press their new advantage, the Russians were pouring forces into the east. In America, Mr. Trump, a Ukraine skeptic, was mid-political resurrection; some congressional Republicans were grumbling about cutting off funding.

A year ago, the coalition had been talking victory. As 2024 arrived and ground on, the Biden administration would find itself forced to keep crossing its own red lines simply to keep the Ukrainians afloat.

But first, the immediate business in Wiesbaden: Generals Cavoli and Aguto explained that they saw no plausible path to reclaiming significant territory in 2024. The coalition simply couldn’t provide all the equipment for a major counteroffensive. Nor could the Ukrainians build an army big enough to mount one.

The Ukrainians would have to temper expectations, focusing on achievable objectives to stay in the fight while building the combat power to potentially mount a counteroffensive in 2025: They would need to erect defensive lines in the east to prevent the Russians from seizing more territory. And they would need to reconstitute existing brigades and fill new ones, which the coalition would help train and equip.

Mr. Zelensky voiced his support.

Yet the Americans knew he did so grudgingly. Time and again Mr. Zelensky had made it clear that he wanted, and needed, a big win to bolster morale at home and shore up Western support.

Just weeks before, the president had instructed General Zaluzhny to push the Russians back to Ukraine’s 1991 borders by fall of 2024. The general had then shocked the Americans by presenting a plan to do so that required five million shells and one million drones. To which General Cavoli had responded, in fluent Russian, “From where?”

Several weeks later, at a meeting in Kyiv, the Ukrainian commander had locked General Cavoli in a Defense Ministry kitchen and, vaping furiously, made one final, futile plea. “He was caught between two fires, the first being the president and the second being the partners,” said one of his aides.

As a compromise, the Americans now presented Mr. Zelensky with what they believed would constitute a statement victory — a bombing campaign, using long-range missiles and drones, to force the Russians to pull their military infrastructure out of Crimea and back into Russia. It would be code-named Operation Lunar Hail.

Until now, the Ukrainians, with help from the C.I.A. and the U.S. and British navies, had used maritime drones, together with long-range British Storm Shadow and French SCALP missiles, to strike the Black Sea Fleet. Wiesbaden’s contribution was intelligence.

But to prosecute the wider Crimea campaign, the Ukrainians would need far more missiles. They would need hundreds of ATACMS.

At the Pentagon, the old cautions hadn’t melted away. But after General Aguto briefed Mr. Austin on all that Lunar Hail could achieve, an aide recalled, he said: “OK, there’s a really compelling strategic objective here. It isn’t just about striking things.”

Mr. Zelensky would get his long-pined-for ATACMS. Even so, one U.S. official said, “We knew that, in his heart of hearts, he still wanted to do something else, something more.”

General Zabrodskyi was in the Wiesbaden command center in late January when he received an urgent message and stepped outside.

When he returned, gone pale as a ghost, he led General Aguto to a balcony and, pulling on a Lucky Strike, told him that the Ukrainian leadership struggle had reached its denouement: General Zaluzhny was being fired. The betting was on his rival, General Syrsky, to ascend.

The Americans were hardly surprised; they had been hearing ample murmurings of presidential discontent. The Ukrainians would chalk it up to politics, to fear that the widely popular General Zaluzhny might challenge Mr. Zelensky for the presidency. There was also the Stavka meeting, where the president effectively kneecapped General Zaluzhny, and the general’s subsequent decision to publish a piece in The Economist declaring the war at a stalemate, the Ukrainians in need of a quantum technological breakthrough. This even as his president was calling for total victory.

General Zaluzhny, one American official said, was a “dead man walking.”

General Syrsky’s appointment brought hedged relief. The Americans believed they would now have a partner with the president’s ear and trust; decision-making, they hoped, would become more consistent.

General Syrsky was also a known commodity.

Part of that knowledge, of course, was the memory of 2023, the scar of Bakhmut — the way the general had sometimes spurned their recommendations, even sought to undermine them. Still, colleagues say, Generals Cavoli and Aguto felt they understood his idiosyncrasies; he would at least hear them out, and unlike some commanders, he appreciated and typically trusted the intelligence they provided.

For General Zabrodskyi, though, the shake-up was a personal blow and a strategic unknown. He considered General Zaluzhny a friend and had given up his parliamentary seat to become his deputy for plans and operations. (Soon he would be pushed out of that job, and his Wiesbaden role. When General Aguto found out, he called with a standing invitation to his North Carolina beach house; the generals could go sailing. “Maybe in my next life,” General Zabrodskyi replied.)

And the changing of the guard came at a particularly uncertain moment for the partnership: Goaded by Mr. Trump, congressional Republicans were holding up $61 billion in new military aid. During the battle for Melitopol, the commander had insisted on using drones to validate every point of interest. Now, with far fewer rockets and shells, commanders along the front adopted the same protocol. Wiesbaden was still churning out points of interest, but the Ukrainians were barely using them.

“We don’t need this right now,” General Zabrodskyi told the Americans.

The red lines kept moving.

There were the ATACMS, which arrived secretly in early spring, so the Russians wouldn’t realize Ukraine could now strike across Crimea.

And there were the SMEs. Some months earlier, General Aguto had been allowed to send a small team, about a dozen officers, to Kyiv, easing the prohibition on American boots on Ukrainian ground. So as not to evoke memories of the American military advisers sent to South Vietnam in the slide to full-scale war, they would be known as “subject matter experts.” Then, after the Ukrainian leadership shake-up, to build confidence and coordination, the administration more than tripled the number of officers in Kyiv, to about three dozen; they could now plainly be called advisers, though they would still be confined to the Kyiv area.

Perhaps the hardest red line, though, was the Russian border. Soon that line, too, would be redrawn.

In April, the financing logjam was finally cleared, and 180 more ATACMS, dozens of armored vehicles and 85,000 155-millimeter shells started flowing in from Poland.

Coalition intelligence, though, was detecting another sort of movement: Components of a new Russian formation, the 44th Army Corps, moving toward Belgorod, just north of the Ukrainian border. The Russians, seeing a limited window as the Ukrainians waited to have the American aid in hand, were preparing to open a new front in northern Ukraine.

The Ukrainians believed the Russians hoped to reach a major road ringing Kharkiv, which would allow them to bombard the city, the country’s second-largest, with artillery fire, and threaten the lives of more than a million people.

The Russian offensive exposed a fundamental asymmetry: The Russians could support their troops with artillery from just across the border; the Ukrainians couldn’t shoot back using American equipment or intelligence.

Yet with peril came opportunity. The Russians were complacent about security, believing the Americans would never let the Ukrainians fire into Russia. Entire units and their equipment were sitting unsheltered, largely undefended, in open fields.

The Ukrainians asked for permission to use U.S.-supplied weapons across the border. What’s more, Generals Cavoli and Aguto proposed that Wiesbaden help guide those strikes, as it did across Ukraine and in Crimea — providing points of interest and precision coordinates.

The White House was still debating these questions when, on May 10, the Russians attacked.

This became the moment the Biden administration changed the rules of the game. Generals Cavoli and Aguto were tasked with creating an “ops box” — a zone on Russian soil in which the Ukrainians could fire U.S.-supplied weapons and Wiesbaden could support their strikes.

At first they advocated an expansive box, to encompass a concomitant threat: the glide bombs — crude Soviet-era bombs transformed into precision weapons with wings and fins — that were raining terror on Kharkiv. A box extending about 190 miles would let the Ukrainians use their new ATACMS to hit glide-bomb fields and other targets deep inside Russia. But Mr. Austin saw this as mission creep: He did not want to divert ATACMS from Lunar Hail.

Instead, the generals were instructed to draw up two options — one extending about 50 miles into Russia, standard HIMARS range, and one nearly twice as deep. Ultimately, against the generals’ recommendation, Mr. Biden and his advisers chose the most limited option — but to protect the city of Sumy as well as Kharkiv, it followed most of the country’s northern border, encompassing an area almost as large as New Jersey. The C.I.A. was also authorized to send officers to the Kharkiv region to assist their Ukrainian counterparts with operations inside the box.

The box went live at the end of May. The Russians were caught unawares: With Wiesbaden’s points of interest and coordinates, as well as the Ukrainians’ own intelligence, HIMARS strikes into the ops box helped defend Kharkiv. The Russians suffered some of their heaviest casualties of the war.

The unthinkable had become real. The United States was now woven into the killing of Russian soldiers on sovereign Russian soil.

Summer 2024: Ukraine’s armies in the north and east were stretched dangerously thin. Still, General Syrsky kept telling the Americans, “I need a win.”

A foreshadowing had come back in March, when the Americans discovered that Ukraine’s military intelligence agency, the HUR, was furtively planning a ground operation into southwest Russia. The C.I.A. station chief in Kyiv confronted the HUR commander, Gen. Kyrylo Budanov: If he crossed into Russia, he would do so without American weapons or intelligence support. He did, only to be forced back.

At moments like these, Biden administration officials would joke bitterly that they knew more about what the Russians were planning by spying on them than about what their Ukrainian partners were planning.

To the Ukrainians, though, “don’t ask, don’t tell,” was “better than ask and stop,” explained Lt. Gen. Valeriy Kondratiuk, a former Ukrainian military intelligence commander. He added: “We are allies, but we have different goals. We protect our country, and you protect your phantom fears from the Cold War.”

In August in Wiesbaden, General Aguto’s tour was coming to its scheduled end. He left on the 9th. The same day, the Ukrainians dropped a cryptic reference to something happening in the north.

On Aug. 10, the C.I.A. station chief left, too, for a job at headquarters. In the churn of command, General Syrsky made his move — sending troops across the southwest Russian border, into the region of Kursk.

For the Americans, the incursion’s unfolding was a significant breach of trust. It wasn’t just that the Ukrainians had again kept them in the dark; they had secretly crossed a mutually agreed-upon line, taking coalition-supplied equipment into Russian territory encompassed by the ops box, in violation of rules laid down when it was created.

The box had been established to prevent a humanitarian disaster in Kharkiv, not so the Ukrainians could take advantage of it to seize Russian soil. “It wasn’t almost blackmail, it was blackmail,” a senior Pentagon official said.

The Americans could have pulled the plug on the ops box. Yet they knew that to do so, an administration official explained, “could lead to a catastrophe”: Ukrainian soldiers in Kursk would perish unprotected by HIMARS rockets and U.S. intelligence.

Kursk, the Americans concluded, was the win Mr. Zelensky had been hinting at all along. It was also evidence of his calculations: He still spoke of total victory. But one of the operation’s goals, he explained to the Americans, was leverage — to capture and hold Russian land that could be traded for Ukrainian land in future negotiations.

Provocative operations once forbidden were now permitted.

Before General Zabrodskyi was sidelined, he and General Aguto had selected the targets for Operation Lunar Hail. The campaign required a degree of hand-holding not seen since General Donahue’s day. American and British officers would oversee virtually every aspect of each strike, from determining the coordinates to calculating the missiles’ flight paths.

Of roughly 100 targets across Crimea, the most coveted was the Kerch Strait Bridge, linking the peninsula to the Russian mainland. Mr. Putin saw the bridge as powerful physical proof of Crimea’s connection to the motherland. Toppling the Russian president’s symbol had, in turn, become the Ukrainian president’s obsession.

It had also been an American red line. In 2022, the Biden administration prohibited helping the Ukrainians target it; even the approaches on the Crimean side were to be treated as sovereign Russian territory. (Ukrainian intelligence services tried attacking it themselves, causing some damage.)

But after the partners agreed on Lunar Hail, the White House authorized the military and C.I.A. to secretly work with the Ukrainians and the British on a blueprint of attack to bring the bridge down: ATACMS would weaken vulnerable points on the deck, while maritime drones would blow up next to its stanchions.

But while the drones were being readied, the Russians hardened their defenses around the stanchions.

The Ukrainians proposed attacking with ATACMS alone. Generals Cavoli and Aguto pushed back: ATACMS alone wouldn’t do the job; the Ukrainians should wait until the drones were ready or call off the strike.

In the end, the Americans stood down, and in mid-August, with Wiesbaden’s reluctant help, the Ukrainians fired a volley of ATACMS at the bridge. It did not come tumbling down; the strike left some “potholes,” which the Russians repaired, one American official grumbled, adding, “Sometimes they need to try and fail to see that we are right.”

The Kerch Bridge episode aside, the Lunar Hail collaboration was judged a significant success. Russian warships, aircraft, command posts, weapons depots and maintenance facilities were destroyed or moved to the mainland to escape the onslaught.

For the Biden administration, the failed Kerch attack, together with a scarcity of ATACMS, reinforced the importance of helping the Ukrainians use their fleet of long-distance attack drones. The main challenge was evading Russian air defenses and pinpointing targets.

Longstanding policy barred the C.I.A. from providing intelligence on targets on Russian soil. So the administration would let the C.I.A. request “variances,” carve-outs authorizing the spy agency to support strikes inside Russia to achieve specific objectives.

Intelligence had identified a vast munitions depot in the lakeside town of Toropets, some 290 miles north of the Ukrainian border, that was providing weapons to Russian forces in Kharkiv and Kursk. The administration approved the variance. Toropets would be a test of concept.

C.I.A. officers shared intelligence about the depot’s munitions and vulnerabilities, as well as Russian defense systems on the way to Toropets. They calculated how many drones the operation would require and charted their circuitous flight paths.

On Sept. 18, a large swarm of drones slammed into the munitions depot. The blast, as powerful as a small earthquake, opened a crater the width of a football field. Videos showed immense balls of flame and plumes of smoke rising above the lake.

A munitions depot in Toropets, Russia. Maxar Technologies

The depot after a drone strike assisted by the C.I.A. Maxar Technologies

Yet as with the Kerch Bridge operation, the drone collaboration pointed to a strategic dissonance.

The Americans argued for concentrating drone strikes on strategically important military targets — the same sort of argument they had made, fruitlessly, about focusing on Melitopol during the 2023 counteroffensive. But the Ukrainians insisted on attacking a wider menu of targets, including oil and gas facilities and politically sensitive sites in and around Moscow (though they would do so without C.I.A. help).

“Russian public opinion is going to turn on Putin,” Mr. Zelensky told the American secretary of state, Antony Blinken, in Kyiv in September. “You’re wrong. We know the Russians.”

Mr. Austin and General Cavoli traveled to Kyiv in October. Year by year, the Biden administration had provided the Ukrainians with an ever-more-sophisticated arsenal of weaponry, had crossed so many of its red lines. Still, the defense secretary and the general were worrying about the message written in the weakening situation on the ground.

The Russians had been making slow but steady progress against depleted Ukrainian forces in the east, toward the city of Pokrovsk — their “big target,” one American official called it. They were also clawing back some territory in Kursk. Yes, the Russians’ casualties had spiked, to between 1,000 and 1,500 a day. But still they kept coming.

Mr. Austin would later recount how he contemplated this manpower mismatch as he looked out the window of his armored S.U.V. snaking through the Kyiv streets. He was struck, he told aides, by the sight of so many men in their 20s, almost none of them in uniform. In a nation at war, he explained, men this age are usually away, in the fight.

This was one of the difficult messages the Americans had come to Kyiv to deliver, as they laid out what they could and couldn’t do for Ukraine in 2025.

Mr. Zelensky had already taken a small step, lowering the draft age to 25. Still, the Ukrainians hadn’t been able to fill existing brigades, let alone build new ones.

Mr. Austin pressed Mr. Zelensky to take the bigger, bolder step and begin drafting 18-year-olds. To which Mr. Zelensky shot back, according to an official who was present, “Why would I draft more people? We don’t have any equipment to give them.”

“And your generals are reporting that your units are undermanned,” the official recalled Mr. Austin responding. “They don’t have enough soldiers for the equipment they have.”

That was the perennial standoff:

In the Ukrainians’ view, the Americans weren’t willing to do what was necessary to help them prevail.

In the Americans’ view, the Ukrainians weren’t willing to do what was necessary to help themselves prevail.

Mr. Zelensky often said, in response to the draft question, that his country was fighting for its future, that 18- to 25-year-olds were the fathers of that future.

To one American official, though, it’s “not an existential war if they won’t make their people fight.”

General Baldwin, who early on had crucially helped connect the partners’ commanders, had visited Kyiv in September 2023. The counteroffensive was stalling, the U.S. elections were on the horizon and the Ukrainians kept asking about Afghanistan.

The Ukrainians, he recalled, were terrified that they, too, would be abandoned. They kept calling, wanting to know if America would stay the course, asking: “What will happen if the Republicans win the Congress? What is going to happen if President Trump wins?’”

He always told them to remain encouraged, he said. Still, he added, “I had my fingers crossed behind my back, because I really didn’t know anymore.”

Mr. Trump won, and the fear came rushing in.

In his last, lame-duck weeks, Mr. Biden made a flurry of moves to stay the course, at least for the moment, and shore up his Ukraine project.

He crossed his final red line — expanding the ops box to allow ATACMS and British Storm Shadow strikes into Russia — after North Korea sent thousands of troops to help the Russians dislodge the Ukrainians from Kursk. One of the first U.S.-supported strikes targeted and wounded the North Korean commander, Col. Gen. Kim Yong Bok, as he met with his Russian counterparts in a command bunker.

The administration also authorized Wiesbaden and the C.I.A. to support long-range missile and drone strikes into a section of southern Russia used as a staging area for the assault on Pokrovsk, and allowed the military advisers to leave Kyiv for command posts closer to the fighting.

In December, General Donahue got his fourth star and returned to Wiesbaden as commander of U.S. Army Europe and Africa. He had been the last American soldier to leave in the chaotic fall of Kabul. Now he would have to navigate the new, unsure future of Ukraine.

So much had changed since General Donahue left two years before. But when it came to the raw question of territory, not much had changed. In the war’s first year, with Wiesbaden’s help, the Ukrainians had seized the upper hand, winning back more than half of the land lost after the 2022 invasion. Now, they were fighting over tiny slivers of ground in the east (and in Kursk).

One of General Donahue’s main objectives in Wiesbaden, according to a Pentagon official, would be to fortify the brotherhood and breathe new life into the machine — to stem, perhaps even push back, the Russian advance. (In the weeks that followed, with Wiesbaden providing points of interest and coordinates, the Russian march toward Pokrovsk would slow, and in some areas in the east, the Ukrainians would make gains. But in southwest Russia, as the Trump administration scaled back support, the Ukrainians would lose most of their bargaining chip, Kursk.)

In early January, Generals Donahue and Cavoli visited Kyiv to meet with General Syrsky and ensure that he agreed on plans to replenish Ukrainian brigades and shore up their lines, the Pentagon official said. From there, they traveled to Ramstein Air Base, where they met Mr. Austin for what would be the final gathering of coalition defense chiefs before everything changed.

With the doors closed to the press and public, Mr. Austin’s counterparts hailed him as the “godfather” and “architect” of the partnership that, for all its broken trust and betrayals, had sustained the Ukrainians’ defiance and hope, begun in earnest on that spring day in 2022 when Generals Donahue and Zabrodskyi first met in Wiesbaden.

Mr. Austin is a solid and stoic block of a man, but as he returned the compliments, his voice caught.

“Instead of saying farewell, let me say thank you,” he said, blinking back tears. And then added: “I wish you all success, courage and resolve. Ladies and gentlemen, carry on.”