კენი დალგლიში თავის წიგნში დინამოსთან თამაშს იხსენებს. ჩვენებს ენფილდზე თამაშის დაწყებამდე მოთელვა თავხედურად კოპის (მაგათი სამხრეთის ტრიბუნაა, ყველაზე გადარეული ფანები მანდ სხდებიან) წინ გაუკეთებიათ. როგორც წესი, სტუმრები ამას ერიდებიან. დინამომ ეს ან არ იცოდა, ან ფარსადანოვიჩმა სპეციალურად გააკეთებინა, რომ ეჩვენებინა, თქვენი არ გვეშინიაო. დალგლიში ამბობს, სუნესს ვუთხარი, რახან ამის ჩვენება უნდათ, ეტყობა, მართლა ეშინიათო.

გვაიძულეს თბილისში მოსკოვის გავლით ჩავფრენილიყავით აეროფლოტის თვითმფრინავებითო. თბილისს ეძახის one of the grimmest parts of Europe, even by Communist standards.

ლივერპული თბილისში რომელ სასტუმროში გაჩერდა, აჭარაში თუ ივერიაში? დიდ ვერაფერი სასტუმრო იყოო, თუმცა გვითხრეს, თბილისში საუკეთესოაო. ლიფტში არ ვსხდებოდით, რაღაც ხვრელები იყო და წყალი ჩამოდიოდაო. მზარეულს არ ვენდობოდით, ჩვენი ჩამოვიყვანეთო. ადგილობრივს ვისკი ვაჩუქეთ და ბედნიერი იყო, რადგან საქართველოში გაჭირვება იყოო.

გულშემატკივრებმა ღამით არ დაგვაძინეს, დინამო, დინამოს ყვიროდნენო. ეტყობოდა, ხელისუფლების სანქცირებული იყო, თორემ სსრკ-ში ხალხს ეგრე შეკრების ნებას ვინ მისცემდაო.

აი, კიდევ: The whole experience was eye-opening and anyone travelling behind the Iron Curtain with thoughts about communism being the future would have changed their mind sharpish. Power to the people? Many didn’t even have electrical power. Accommodation was decrepit, food short and the whole place seemed blanketed in a cloud of smog and depression. Who’d want to live like that? I never blamed the Georgian people, who were just trapped in a brutal system.

ბოლოს ამბობს, დინამომ საუცხოო ფეხბურთი ითამაშაო: Dinamo stormed to a 3–0 win, playing some wonderful football in the second half, which we simply couldn’t live with

=========================================

სრული ტექსტი:

Fortunately for us, the party got going again quickly back

then. That League success swept us back into the

European Cup, thank God, as we’d really missed the

competition. Liverpool belong in the European Cup. Sadly,

we didn’t last long in the 79–80 season after being thrown

in against Dinamo Tbilisi in the first round. Over the years, I

feel a myth has grown unchecked that Dinamo had so little

fear of Liverpool they cockily warmed up in front of the Kop.

Newspapers were riddled with idle chatter that Liverpool

supporters apparently marvelled at the Georgians’ skills

before the first leg on 19 September.

‘If they were doing it to show they weren’t afraid, that just

proves to me they were afraid,’ I said to Graeme. We won,

but only 2–1, and a fortnight later set out on a journey into

the unknown.

Liverpool’s plane was an Aeroflot jet, which the Soviets

insisted we hired, conveniently making them a bundle of

roubles. For a bunch of communists, I felt they showed

distinct capitalist tendencies. Our journey became

increasingly complicated as the Iron Curtain still hung

across the Continent, and any destination in the Soviet

Union involved a stop in Moscow – another Soviet demand.

So we dutifully filed out of the plane, heading through

immigration as Red Army soldiers scrutinised us as if we

were some band of dissidents. The stopover seemed

pretty pointless, paranoid even, but we shrugged and got

on with it. The Soviet solders and immigration officials

didn’t look the types who’d welcome any friendly banter.

We then reboarded the plane to Tbilisi, landing in one of

the grimmest parts of Europe, even by Communist

standards.

Liverpool’s hotel was pretty basic but we were assured it

was Tbilisi’s finest. Fortunately, Bob always made sure we

came well-prepared, bringing our own chefs, Harry White

and Alan Glynn, who worked in the hotel trade in Dublin.

Harry and Alan ensured we had tea and toast for breakfast

and that the hotel cook was onside, a vital move. I was

always suspicious about what foreign cooks might slip into

the food but Harry and Alan man-marked the cook closely,

watching him in the hotel, keeping him sweet with a bottle

of whisky or two. European football required intelligent

tactics off the field as well as on.

‘Anything we don’t use, you can keep,’ Harry and Alan

told the cook, who was incredibly grateful, because

provisions were modest in Georgia. Tbilisi was pretty

primitive.

‘Be careful in the lift,’ I told the players after one perilous

descent towards reception. ‘There’s water streaming down

the side. Don’t go near the electrics.’

‘It’s a hole,’ seemed to be the overwhelming verdict of

the players – a noisy hole as well. Under a Soviet regime

that didn’t seem big on laughs, the natives of Georgia were

forbidden from staging demonstrations – until Liverpool

arrived. My precious sleep was disturbed at 2 a.m. by

chants of ‘Dinamo, Dinamo’. Peering out of the window, I

saw hundreds of people marching up and down outside our

hotel. The noisy protest was so obviously organised it must

have been sanctioned by the Soviet authorities. The

Georgians would never have dared gather in numbers like

that without permission from Moscow.

During my trips behind the Iron Curtain, I gained the

strong impression these Soviets used the European Cup

as a vehicle to generate great publicity for all the Soviet

countries. Whenever a western club visited, the

Communists wanted a show of strength, and that meant

giving their sides every chance of winning. Liverpool were

not just up against a team in Tbilisi. We were up against an

ideology. The whole experience was eye-opening and

anyone travelling behind the Iron Curtain with thoughts

about communism being the future would have changed

their mind sharpish. Power to the people? Many didn’t even

have electrical power. Accommodation was decrepit, food

short and the whole place seemed blanketed in a cloud of

smog and depression. Who’d want to live like that? I never

blamed the Georgian people, who were just trapped in a

brutal system. In the morning, some of the locals even

queued around the hotel just to see what westerners looked

like.

The Georgians’ sad, controlled existence meant they

really let rip on match-day. Dinamo Tbilisi fans were

incredibly passionate, leaping out of the stands, running to

the edge of the pitch as their team gave them plenty to

cheer. Dinamo stormed to a 3–0 win, playing some

wonderful football in the second half, which we simply

couldn’t live with, and again Liverpool crashed out of

Europe at the first hurdle. Even the refreshment in the

dressing room looked trouble.

‘Don’t touch the tea,’ said Bob, ‘you don’t know what

they’ve put in it.’

This post has been edited by Count Szegedi on 11 May 2015, 20:06

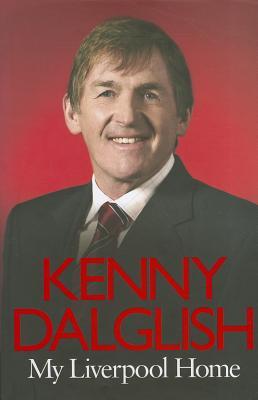

მიმაგრებული სურათი

·

·